Back to main text of Chapter 6

SOLVING THE LAND PROBLEM

A serious difficulty for many community projects is getting affordable access to suitable buildings and land. Robert Swann and Susan Witt of the Schumacher Society in the United States believe that this problem is part of a much larger one and that it will not be possible to build satisfactory self-reliant local economies unless land ownership ceases to be a legitimate arena for financial speculation.

|

When a region has excess capital, that capital can work to draw out the imaginative and entrepreneurial skills of its people and thus generate new businesses producing goods and services once imported from other regions....When the capital is tied up in land, however, the local economy chokes up. Credit for the small business owner tightens. The region loses its diversity, which is the basis of a more sustainable economy and of a more environmentally-responsible business sector57.

As mentioned in Chapter Three, Swann once worked with Ralph Borsodi, a leader of the back-to-the-land movement in the United States in the 1930s. In an essay, The Possessional Problem,58 which provides the intellectual foundation for most American community land trust thinking along with Henry George's 1879 book Progress and Poverty, Borsodi makes a distinction between things that it is morally correct for someone to own and those that should be held in trust. For him, it is moral to treat things one grows or makes as one's private property and to buy or sell them, but the land itself and the Earth's resources should be held in trust and their use regulated to benefit this and future generations.

"None of the governments which now claim sovereignty over the Earth can vindicate in rational and moral terms.... the issuance of title [to land] 'in fee simple absolute'; therefore, we must face the problem of how land and other resources should be allocated.....Since capitalism takes private ownership for granted, it ignores both the question of its moral validity and its economic utility. As I see it, capitalism is from beginning to end a rationalization.To justify having everything privately owned, including what should be held in trust - the airwaves for instance, or mineral resources - its proponents have to accept all sorts of qualifications of the doctrine and all sorts of government intervention and regulation of business operations."

Many people have thought along similar lines, of course, and gone on to suggest that land and mineral resources be nationalised. This suggestion seemed as misguided to Borsodi as it does to Swann, who thinks that the centralised management of state-controlled land has been as big a disaster as the almost totally unregulated dealing in land on the open market. Instead, Swann wants to see land and resources owned by democratic community organisations whose membership would be open to any resident of the district or bio-region. He suggests that one third of the directors of a trust should be elected from amongst the leaseholding members - that is, those who are using the land the trust owns - one third from non-leaseholders - in other words, the wider community - and that the final third be professionals such as land-use planners or lawyers appointed jointly by the elected directors so that the trust can have the benefit of their expertise.

In 1967 Swann and Borsodi set up the International Independence Institute to promote community ownership of land and to support Vinoba Bhave and other workers in the Gramdan (Village Gift) movement who walked from village to village in rural India appealing to landowners to give part of their holdings to community organisations to be leased to landless labourers to farm. Many landowners responded to the campaign and the organisations set up to adminster the land they gave were the forerunners of the community land trusts in the United States. Swann then worked with Slater King, a cousin of Martin Luther King, and New Communities, a group from Albany, Georgia, to set up a land trust for African-Americans in the rural South who were unable to get land to farm and were consequently forced to migrate to the northern cities to look for work. With donations and loans, New Communities purchased 5,000 acres and leased it out as individual homesteads and farms for co-operatives using the legal structure devised by the Jewish National Fund which began to acquire land in Palestine at the turn of this century and now owns 95% of Israel.

Not all went well however. "Through a series of tragic deaths, much of the original leadership was lost and promised grants fell through" Susan Witt says. "The inventor of xerography had promised a million dollars but died suddenly before signing the cheque and his wife gave his fortune to the California Zen center. As a result, New Communities took on more debt than was wise to purchase the land and were unable to repay the mortgage. They lost the property several years ago. But although the first land trust failed, it started a movement."

Swann set up the Institute for Community Economics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1977 to promote land trusts and the idea of social investment. "By 1980, Bob and I were the only staff. I worked in a factory in the mornings to support us and then went to the office in the afternoon" Witt says."That spring we were asked to the Berkshires to start a community land trust and were talked into staying. The prospect of living and working on a community land trust rather than just telling others to do it was very appealing to us". The new trust, the Community Land Trust in the Southern Berkshires, attracted some donations, took out a loan and bought a ten-acre apple orchard outside the small town of Great Barrington the following year. It then leased out four house sites on part of the property, one of them to Witt and Swann for a house they built themselves, and has since used the lease fees to pay off the mortgage.

"The Trust leases the rest of the orchard separately to a farmer who bought the existing trees and also owns the new raspberry canes, asparagus and fruit trees he has planted" Witt says. "No farmer could have paid as much for the orchard as was available for it on the housing market and, if it had not been bought by the Trust but divided up into four one-house properties, it would have gone out of horticulture. The lease fee the farmer pays is minimal so the Trust has secured an affordable source of food production in the region."

If the farmer or the people who have leased house sites wish to move on, they can sell whatever they have done on the property. "With a trust, you don't own the land but you do own the house and any improvements such as planted trees" Swann says. "However you cannot necessarily sell them at market value. An owner who wishes to sell is obliged to offer them to the trustees who are only obliged to pay replacement value."

Since buying the orchard, the Trust has acquired two other properties. One is an old house on the bank of the Housatonic river in Great Barrington which has been converted into office space for several community organisations. The other is Forest Row, 21 acres of woodland on the edge of the town. Most of this is to be preserved but five acres have been used for eighteen moderately-priced houses, each of which was designed and built specifically for the site lease holder. "Even with careful planning and the unit holder's participation, the Trust was unable to keep purchase costs as low as it would have liked" Swann says. Accordingly, he helped set up a charity, the Fund for Affordable Housing, which used donations to subsidise the construction of two of the houses at Forest Row so that they were available to a lower income group.

Despite these successes and the establishment of over a hundred similar land trusts throughout the United States, Swann and Witt are disappointed at the rate of progress. "Unfortunately, the accumulation of land in community land trusts has been very gradual" they write in the position paper. "It is true that each new piece of land in a CLT has its own story of hope and good work, yet there is no broad movement to decommoditize land. Environmentalism is the new religion of our age, but it is only a Sunday morning religion... [because] we still reserve the right to sell the land we own and care for to the highest bidder. We have yet to fully imagine and embrace a culture in which land use is allocated by social and environmental contract rather than by checkbook." Click for 2002 update by Caroline Whyte

There are very few land trusts in Britain and Ireland. One of the oldest must be that set up on the island of Lewis by Lord Leverhulme, a founder of the Lever Brothers soap company which eventually merged with a Dutch margarine company to become Unilever. Leverhulme bought Lewis in 1917 and prepared ambitious plans for, among other things, developing the island's fishing industry to supply his Mac Fisheries chain of fish shops. However, his ideas ran into fierce opposition from a powerful group of locals, and by 1923 he was ready to give up. In order to wind up his affairs, he offered to give his tenants and crofters, free of charge, full freehold titles to the land they were renting from him. For various reasons, few of them took up his offer, but Stornoway Town Council accepted the deeds to the town itself, the parish of Stornoway and a small part of a neighbouring parish, and the Stornoway Trust was set up to administer Leverhulme's former property. Apart from land it has since sold outright to the council, the Trust has maintained the freehold of everything it took over. Only those who live on its property and whose names appear on the parliamentary Register of Electors have the right to vote in the elections for the ten positions on its board of trustees and at present, the trustees, all of whom live locally, have a policy of giving the Trust's income from rents, interest and quarry royalties away to local charities and employment creation schemes. Recently, the Trust has been granting long leases to quarter-acre house sites for only £50.

Three other land trusts have been set up in Scotland over the past few years; many more can be expected to be formed before the end of the decade as a result of an announcement early in 1996 by the Secretary of State for Scotland, Michael Forsyth, that the government was prepared to transfer its 260,000 acres of state-owned crofting estates free of charge to trusts if the 1368 crofter-tenants could show that the new bodies would not need a continuing financial contribution from the public purse. Indeed, the main reason for the offer was that the Exchequer was making a loss on running the estates - largely, a Scottish Crofter's Union survey had shown, because of the Scottish Office's bureaucratic procedures. Another factor, however, was that crofters in Assynt, Melness and in Borve on the island of Skye had shown that trusts could take over holding from private landlords and manage them more efficiently.

'We had a first-class landlord. We regarded him as a gentleman and a friend,' John MacKenzie, who played a key role in establishing the Borve trust, told me. 'The family had charged the same rents - £5 a year for fifteen or sixteen acres plus the right to use common grazing - from the time the crofts were first settled in 1906.' As a result, there was little incentive for the crofters to take over the property. What changed the situation was the Crofter Forestry Act, which gave them the right to own any trees they might grow on their holdings. Previously, trees had belonged to the landlord. 'Our landlord, Major J.L. MacDonald, is a Skye man and speaks Gaelic, although he made his fortune in London as a financier. He was fiercely opposed to the Act, and as we wanted to be among the first crofters to take advantage of the grants available for afforestation because sometimes the early birds get freebies from people anxious to make their schemes work, the idea emerged that we should buy him out'.

After some delay, MacDonald said that he wanted £40,000 for the 4,000 acre property. much more than the £14,000 that the crofters could have expected to pay if they had fought the purchase through the courts - in a previous case, crofters had been able to purchase their holdings for fifteen times the annual rent. 'If the Major had been a bad landlord or an absentee one, we would have taken pleasure in fighting him, but we offered £20,000 and we heard in June 1993 that he had accepted. The whole thing was very amicable. We gave him back the shooting rights out of goodwill, not that there's much to shoot around here anyway. We got a short-term bridging loan from the Highland Fund to pay him and the local enterprise company paid our legal costs'.

Although by law they could never have been evicted from their holdings, actually owning them, albeit indirectly through a trust, seems to have made a big psychological difference to the people of Borve. 'It gives a feeling of freedom that no Act of Parliament could ever give,' MacKenzie says. In fact, holding the whole property jointly with their neighbours has given them something that the private ownership of individual parcels would not: the challenge of developing it as a whole. 'It would have been easy to have sat back and said "Now we have what we wanted" and just carried on working at our daily occupations,' he continues. 'But the ownership of the land brings new responsibilities and new challenges. How could we as landowners protect the environment, improve the grazings and also generate some income from a source other than grazing animals?'

The crofters' first joint project was to plant a fifty-acre woodland of mixed native species along one of the property's boundaries. 'It will soon provide shelter for sheep and cattle and food and shelter for wildlife,' MacKenzie says. 'More forestry is at the planning stage on an area of the hill that is not of importance to the grazing stock. Now that the ownership of the crofting lands has passed to us it is our responsibility to make sure that people stay on the crofts and that this crofting estate is a pleasant place to live in and provide a suitable environment in which to raise children.'

The psychological change that the new form of land ownership has brought about was mentioned in an editorial in the March 1996 issue of The Crofter, a monthly publication of the Scottish Crofter's Union. 'If you know Crofters who are now part of a trust, one of the things that must strike you is their confidence, and the respect with which they are now seen by others, and indeed themselves. They have gone beyond the barrier of feeling that they as crofters are not capable of running their own affairs. They have proved that as crofters they can get on sufficiently well with each other to co-operate in the management of their estate. They have a pride in their acheivement which sustains them through the unquestionable challenges that confront them in this exciting new era of land ownership.' One aspect of the new confidence is that crofters from Borve and Assynt have collaborated with Highland and Islands Enterprise, the development agency from the area, and the government's Crofter's Commission, to set up the Crofting Trusts Advisory Service, which helps crofters on other estates set up land trusts to take over them too.

Click for 2003 update on Community Land Trusts in Scotland by Caroline Whyte

|

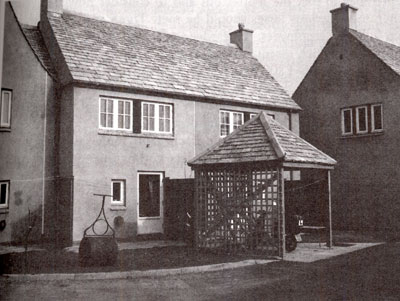

Later, a granny flat was added to one of the houses and another was split into two flats, so the Trust now has six dwellings on the site. Then a second quarter acre site in the village became available and the district council gave the Trust a one-year interest-free loan of £80,000 to enable it to buy it. "We had a track record. We were the only village in West Oxfordshire that had built any affordable housing, even though the county council had offered to give planning approval for the use of farmland for it. They agreed to lend us the money within seven days. I cannot speak too highly of them" Crofts says. There are now five houses on this site, financed in part by Mercury Provident and the Ecology Building Society and in part by gifts and by private ethical investors, who lend their money at a fixed interest rate for ten years. "We advertised in The Friend [a Quaker magazine] for six weeks and it brought in about £85,000. Also, the Quaker Housing trust converted a £20,000 interest-free loan into a grant and attenders at the Witney monthly meeting made donations of £6-7,000" says Crofts, who is a Quaker himself.

"All the houses have been built and insulated to a very high standard so that they are warm and comfortable to live in" he adds. "They are designed for maximum solar gain and we'll put passive solar conservatories on four of them when we have the money. We are able to let them at below market rates to people connected with the village because of the donations and because local people have covenanted to pay a sum each year to cover some of the interest charges, which are very high in the early stages of a loan. We've never had any government money - if we had, we wouldn't have been able to build to the standard we did and we'd have never owned the houses. Because we are a charitable trust, the tenants have no right to buy the houses which will always belong to the village. When we get the loans paid off, we'll be able to bring the rentals down to council-house levels and still have a good income which we plan to use to re-boost social services here which the government has steadily cut back over the past ten years. We're moving towards becoming the Independent Democratic Republic of Stonesfield. We intend to be a standing reproach to the Government and the Treasury by showing that a high standard of social care is possible if you spend your money correctly. Devolution, local control and smallness are important to us."

Other villages had asked the Trust about how they could do something similar, he said, but none of them had been able to cope with the necessary fund-raising which was 'pretty intensive at times.'. "They've all invited outside housing associations to come in and build the houses for them. This means that they will never own them. As far as I know, we're unique."

2002 update on Stonesfield Community Trust by Caroline Whyte

The Stonesfield Community Trust continues to operate successfully. A third stage in its development began in 1993, when Tony Crofts and his wife, Randi Berild, who is an architect and had in fact designed the houses built in the second stage of the trust, bought an old factory in the village that had formerly been used as a silk-screen printing shop. They were aided in the purchase by a government grant intended for creating workspace. The loans they took out to buy the premises are being repaid by the rental income from the businesses that have been established there - a pre-school, a post office and a tele-cottage - and well as two more houses.

After seven years of paying back the bank loan on the property, the bank released its claim on the pre-school property. Crofts and his wife then transferred the ownership of the pre-school to the trust. The rest of the businesses and the two homes are still being paid off. The plan is that once the bank is fully repaid, the income from the properties will provide a pension for Crofts and his wife until they die, after which the money will go to the trust.

People living in the trust buildings have to have a historical connection to the village, and to be able to show that they can't afford to rent accommodation at market rates. Most people move on after 1-3 years, but some tenants are longer term. The trust is still unique in the UK. When asked about his vision for the future, Crofts commented that he wants the trust to be "about where it is now. I don't want to turn it into an octopus with tentacles all over the place". The board of directors has agreed that twelve dwellings is enough for the trust to administer.

Crofts adds, though, that "Our thinking is also developing in other directions. We're now looking to put the three other houses in Glover's Yard, our own home, and a new house we're buying in Bristol, into an industrial provident society in which people can buy shares which produce either dividends or a right to occupation of dwellings owned by the society. A bit like the proven American strategy of Community Land Trusts."

Many thanks to Nadia Johanisova for providing interview notes for this update.

Robert Swann and Susan Witt,�E.F. Schumacher Society, 140 Jug End Rd., Great Barrington, MA 01230, USA. Tel 413-528-1737, e-mail efssociety@aol.com. A handbook of legal documents for establishing a trust is available.

The School of Living,432 Leaman Road, Cochranville, PA 19330, tel 610 593 2346, e-mail SOL@s-o-l.org was set up by Borsodi in 1934 and has administered a land trust since the early 1970s. It has published several pamphlets and booklets on land trusts.

The Institute for Community Economics, 57, School Street, Springfield, MA 01105-1331, tel. 413 746 8660, fax 413 746 8862, e-mail info@iceclt.org, has a number of publications available on Community Land Trusts.

Tony Crofts, Stonesfield Community Trust, Home Close, High Street, Stonesfield, Witney, Oxon, OX8 8PU. Tel + 44 (0)1993 891 686.

Scottish Crofting Foundation (formerly Scottish Crofters' Union), The Steading, Balmacara Square, by Kyle of Lochalsh IV40 8DJ, tel +44 (0)1520 722891, fax +44 (0)1520 722932, e-mail hq@crofting.org.

The Social Land Ownership website "celebrates the size, diversity and range of patterns of common ownership that comprise the social land sector in various parts of the world". It includes detailed descriptions of some of the Scottish land trusts.

Back to main text of Chapter 6

Other Chapter 6 updates| Search | Contents | Foreword | Preface | Introduction |

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 |

| Epilogue | 2002/3 Updates | Links | Site Map |