Let's consider the real implications of the global issues that underlie the interest in renewable energy. First, what actually is sustainable or green? The word sustainability can mean almost anything to anybody and is in danger of going the way of the word community. There is too much "greenwash" about because no one is very clear what the definition of sustainability actually is. There is also a fair amount of propaganda about how we all need to do our little bit, but that's not enough. We have to go a lot further than doing a little bit.

Sustainability is in danger of becoming a marketing device rather than a genuine commitment. Just because you can come up with a product or a solution that helps to save some energy and is financially viable, it doesn't necessarily mean that it is going to save the planet. The development of renewable energy is being driven by business interests that want to make money out of generating more energy when we are already using far too much in developed countries. The real priority is to reduce the amount of energy we consume. However most of the conventional methods of achieving energy efficiency use fossil fuel based insulation products and are often also dangerous. They can be fire hazards, give off toxic fumes, refuse to biodegrade when land filled and tend to pollute the atmosphere during manufacture. As a result, many conventional energy efficient buildings can also suffer from sick building syndrome.

We rely far too much on glues, sealants, membranes and so on which are synthetic, toxic, pollute the environment and often make disassembly very difficult. Many materials that are used in construction today are non-renewable; they leave holes in the ground and cannot easily be recycled. If we continue to consume resources at the present rate, particularly in the construction industry, we will need three or four planets to sustain the current rate of growth. Even if they run on renewable energy, conventional buildings represent an excessive amount of resource consumption.

FOOTPRINT ANALYSIS

Recent studies based on ecological footprint analysis techniques and mass balance studies indicate just how profligate we are in terms of resource use. After grossly misusing nonrenewable resources to feed the construction industry, we then go on to waste a tremendous amount of the material that goes onto building sites. Construction waste is one of the biggest contributors to landfill, itself an environmental problem.

We have a huge number of empty, disused or underused buildings that could meet many of our needs and yet we are under tremendous pressure to build new buildings. A lot of work is done to design new green buildings but these represent only a very small percentage of the stock. Although the real problem is what to do with existing buildings and how to make them less damaging to the environment, surprisingly little work is being done on this. Re-using existing buildings and therefore saving the embodied energy bound up within those buildings and reducing the amount the demolition waste is incredibly important.

There is a real conflict between people in the green design movement who concentrate on energy efficiency and those who feel that health and toxicity is just as important. I feel that the environmental impact of material production both in manufacturing and when installed in buildings is a key issue. We need to think very seriously about what happens to materials when they come to the end of the line, so that they can be dismantled or reused instead of causing pollution through landfill. Many insulation materials are not biodegradable.

POOR PROJECTS

One of our difficulties is that there are now a growing number of demonstration projects that are very much seen as exemplars of the way forward but are in danger of being 'off-message'. In other words they are not necessarily giving the public the right signals about the future. In a way it might seem a bit unfair to attack particular projects when they have worthy intentions. Nevertheless, we have been doing research at Queen's University which has involved looking at a range of innovative projects which are promoted and claimed to be sustainable, green, environmentally friendly, ecological or whatever. When you try to work out what's gone into those projects - and how far they actually come up to the claims they are making - you start to become a bit sceptical about how much they are really helping to tackle environmental problems.

There are a number of very expensive demonstration buildings throughout the UK that have used Millennium funding to provide a demonstration of renewable energy. However, our analysis of these projects has shown that they are not good examples of best practice in many other aspects of green design. Most fail to make good use of passive solar energy and although millions of pounds was spent on the use of renewable energy, they still only meet 75% - 80% of their energy needs from these sources. A lot of concrete and heavy materials were used in their construction on the basis that thermal mass was required. Rarely was the timber in them from properly certified forests.

We have got to get these things right if we are going to teach people what needs to be done in the future. We need to adopt a holistic approach in which we look at the upstream and the downstream impacts of everything that we do. There is no magic to this. You could come along and pay us a lot of money at the University to calculate lots of things like embodied energy, and to do lifecycle analyses and ecological profiling but the basic principles are very simple. If people were to follow them in a very practical and down to earth way you wouldn't necessarily need to do a lot of calculations. It's a question of thinking through the impacts of the decisions that you are making and having a genuine commitment to being as green as possible.

Unfortunately, at the end of the day most architects and clients want to get the building up more than anything else, so that how it is done often becomes secondary.

But I would argue we need to go even further than buildings that are a good attempt at being green, we need to look at how close we can get to zero impact. If we are consuming more resources than we can sustain over the next decades then we have to look at different ways of doing things. It's not necessarily going to be that easy to achieve zero impact buildings. But at least if we set that as a benchmark, as a target, something we are trying to work towards, then we can have some kind of basis on which to judge how far we are able to achieve that aim.

All buildings inevitably are going to use some resources. Do we have to use as much as we normally do and are there other alternatives? Many of the assessment systems currently available to us to evaluate projects are essentially based on existing practice. They are trying to push things a little bit further along, but are not based on a fundamental critique of the way we do things now.

So what sort of things do we need to move towards zero impact building? We can use renewable materials. Renewable means renewable!

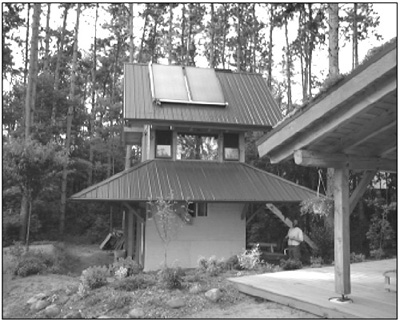

|

Photo - C. Dancey |

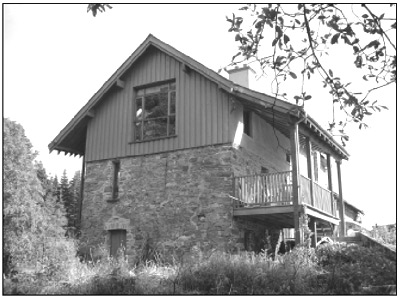

|

Photo - Tom Woolley |

Materials have got to be responsibly sourced. That means not getting them from the other side of the world! I recently talked to some people at a trade exhibition at the RDS in Dublin who were selling granite products and doing extremely well. There is a big upsurge in interest in granite, particularly from the public sector replacing kerbstones in nice urban upgrading schemes. But the granite is coming from China!

Using recycled materials is important but it mustn't lead to the demolition of existing buildings in order to generate high quality architectural salvage when those buildings perhaps themselves ought to be retained and used.

CLAY AND MUD

If we try and create a carbon neutral building, reducing energy as much as possible, there are a range of possible materials which can be used which I would characterise as low impact materials, but not necessarily zero impact materials. For instance, earth. We can use clay and mud forms of construction. This can replace a lot of the materials that we currently use from quarried and highly processed production processes like cement. But earth is not a renewable material, once you have dug it up out of the ground it isn't going to reinvent itself although in small-scale developments you can maybe use the earth that's underneath the building that you need to dig up anyway. So earth is only a low impact material, it is not a zero impact material. On the other hand it has a tremendous potential as a building material and should be considered at all possible times when you are looking for an alternative.

Then there are an awful lot of materials that are made from waste materials such as fly ash. Glass is a material that, if recycled, can be used for building and road construction. There is a lot of work going on around the world using rice husk ash to replace cement and produce very good quality materials. Then there is quite a lot of very interesting work going on using bio-composites and eco-composites. At Queen's, we've been researching materials

|

Architect, John Gilbert. Photo - Tom Woolley |

|

Rachel Bevan Architects. Photo - Tom Woolley |

Farmers have had tremendous problems with what to do with the wool from all their sheep but it could be used as an insulation material and there are a number of companies developing that now. Bamboo is perhaps the most renewable material that you could possibly get. It can grow so quickly that you can actually watch it growing! So if you cut down bamboo it can regenerate itself within 2 to 3 years. There are some remarkably interesting exciting buildings and building products using bamboo. Bamboo can be grown in temperate climates as well. It doesn't just have to be seen as a tropical material.

We have been seeking funding for "The Grow Build Project" where the idea is to see whether it is possible to grow your building. This is not meant to be seen as some kind of peripheral project, but it's to be something that could be part of mainstream construction.

HEMP AND LIME

There is no reason why the kind of experiments we have been doing couldn't be duplicated on a much larger basis, and we have been very excited about the possibilities. We are using composite mixes of hemp and lime, and also hemp and earth. Apart from being a very good, highly insulating and breathable walling material it can also provide an alternative crop for the rural economy and it is adding a great deal of value to something that otherwise is currently just being sold as horse bedding.

In the UK there has been a surge of companies trying to put ecological and environmental building materials onto the market and we have been doing a study funded by the UK Engineering Research Council into the opportunities and obstacles they face. They range from Natural Building Technologies, the Green Building Store that supplies a wide range of products to a company called Eco Solutions that makes a non-toxic form of paint stripper.

A lot of people assume that ecological building solutions will cost more but if buildings are designed and specified correctly from the start there is absolutely no reason why there should be any extra cost. Some materials do, on the face of it appear to cost more, but those costs are going to come down as soon as there is a much bigger take up. If local authorities, for instance, were to really seriously implement green purchasing policies, particularly in the construction sector, that would create a much, much bigger market for the kinds of environmental products which are now becoming available. If they were taken up on a large scale then you would find the cost would come down significantly.

In theory, many renewable products would cost much less than the expensive fossil fuel based synthetic and quarry products.

I am trying to challenge you to think about building in an environmentally responsible, low impact way. We have to make radical changes in the way we build our buildings and what we use to make them if we are really going to start to reduce resource use and materials.

REFERENCES

Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM).

http:// products.bre.co.uk/breeam/default.html

Caleyron N and Woolley T (2002) Overcoming the Barriers to the Greater Development and Use of Environmentally Friendly Construction Materials CIB Sustainable Building Conference Oslo, September.

Centre for Green Building Research. www.qub.ac.uk/arc/research/GreenBuilding/. Centre's Contact: Tel/Fax. 0044 2890 335466. Email. t.woolley@qub.ac.uk

Construction Resources. www.ecoconstruct.com/

DETR. (2000) Building a better Quality of Life. DETR, London.www.sustainable-development.gov.uk/ann_rep/

Egan, J. (1998). Rethinking Construction. DETR, London. www.m4i.org.uk/publications/rethink

EU. Construction Product Directive. http://europa.eu.int/comm/enterprise/construction/

Fairclough, Sir J. (2002). Rethinking Construction Innovation and Research. DTI, London. http://www.dti.gov.uk/construction/main.htm

Forest Stewardship Council. http://www.fsc-uk.demon.co.uk/ FSC

Greenpeace. http://www.greenpeace.org/. Greenpeace Ancient Forest Campaign. http://www.greenpeace.org/pressreleases/forests/2002feb25.html

Kennedy J F , Smith M G and Wanek C. (Eds) (2002) The Art of Natural Building, New Society Publishers, Canada

Malin, N. (2002). Life-cycle Assessment for Buildings: Seeking the Holy Grail. Environmental Building News. March, p.10

National Green Specification (NGS). http://www.greenspec.org.uk. Brian Murphy, contact: BrianSpecMan@aol.com Fax: 01733 238148

Woolley, T., S. Kimmins, P. Harrison, R. Harrison, (1997) Green Building Handbook, Vol. 1. Spon, London.

Woolley T, Kimmins S, (2002) Green Building Handbook Vol 2 Spon Press, London.

This is one of almost 50

chapters and articles in the 336-page large format book, Before the Wells

Run Dry. Copies of the book are available for £9.95 from Green Books. Continue to Part A of Section 7: Ireland's renewable energy resources and its energy demand