This paper is about the realities of operating a renewable energy company selling electricity. It looks at the commercial practicalities of policy decisions and their implications. The title it was suggested I use - 'Should Ireland export green electricity or just sell green credits?' - reminded me of a story I heard from an official in the Department of Trade and Industry in the UK some time back. When the UK was introducing its green credit scheme (which I'll touch on a little later), he got a call from a guy in the Caribbean island of Montserrat, which is under British administration, who wanted to know if he could get renewable green credit value for a scheme he was planning, a 50 megawatt geothermal scheme on the island. Now, the official just happened to know a little about Montserrat, and asked him 'What's the peak electricity demand on the island?' 'Five megawatts.' 'And what are you going to do with a 50 megawatt geo-thermal scheme?' 'That's not important, I'm going to produce all this greenness that I want to sell.'

The man in Montserrat thought that the fact that there was no outlet for the electricity was somewhat irrelevant. I think that is an important point, because we're talking about the electricity market, the energy market, and I think people need to focus on exactly what is meant by green credits and to understand the implications they will have for the market and for the renewable power generation industry.

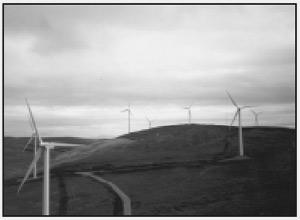

First, though, a brief introduction to airtricity. We are an integrated renewable energy company, active currently in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and Scotland. We have in excess of 2000 megawatts of onshore wind power in development, and we are active offshore in the Arklow Banks project. We have four wind farms currently under contract in the Republic of Ireland, the latest one being with Hibernian Wind Energy which began production in October, 2002. We have a further two under construction. One on King's Mountain, Co. Sligo, is the first transmission-connected wind farm under the new market rules.

The wind farms we own and have constructed have been financed solely on the electricity retail value. This means that they are inherently based on a market risk scenario rather than Alternative Energy Requirement (AER)-type contracts which are supported by a public service obligation framework. This has given us experience in the practicalities of trying to finance long-term, extremely capital-intensive pieces of plant in a market risk scenario where you are talking about a view of the market over the next fifteen years. The implications of EU and government policies are of more than passing interest when you are trying to secure debt for that type of project.

Airtricity is, at least in customer number terms, the largest independent supplier in the all-island market. I use the all-island term because we are active in the North and in the Republic of Ireland; we've been supplying Northern Ireland since July, and in part supplying those customers with renewable energy generated in the Republic. And we also have a track record in the area of green certificates emissions trading. We have done trades into the Dutch and German markets. We are currently developing and are in process of hammering out an innovative renewable obligations certificate with contract in the UK for our first UK farm which should come on stream in the middle of next year. (2003) We also have had some experience in derivative products such as calls and quote options.

|

|

The next picture is of the first offshore measuring mast in Ireland or the UK which is located 10 kilometres off the coast of Arklow, on the Arklow Bank. It's been there since December 2000.

I think it's important to start by getting clear what we mean when we talk about green credits. It's a term that is bounced around a lot, the saviour and major driver of growth in the renewable energy industry, but it's quite a complex area. Then I'll look at the question should Ireland adopt the green credit approach to RES, to use the acronym for renewable energy systems. The implications of green credits are actually quite profound when you adopt a fully market-based approach to the development of the renewable energy industry. And then I will deal with the possibility of Ireland becoming a net exporter of electricity and/or greenness and the commercial risks involved. Airtricity does export but Ireland is not a net exporter of electricity. I think there are lots of practical commercial issues.

The map below is important because it sets out where the wind resources in Europe are, an important consideration when you move to a fully market-based scheme. As it shows, the best resources are in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and Scotland, and that's where Airtricity is active.

|

|

Various support schemes for renewable energy are being used in Europe at present. There is the Refit scheme in Germany, a fixed feed-in tariff available to anyone who connects onto the system. It is quite attractive but it needs to be because of the low wind speeds in Germany. Ireland's AER scheme is a competitive tendering process, similar to the Non Fossil Fuel Obligation (NFFO) one the UK used until recently. And then you have two very different types of green certificate schemes. One type is obligation-based and is now used in the UK. This basically puts an obligation on suppliers of energy to source a certain amount of their energy from renewable schemes and, very importantly, imposes a penalty if they fail. It's a market- based scheme, and with good long-term security: you have the British Government saying that they are committed to this obligation for twenty-six years and so it gives good security to the bank, to the debt-providers, and to us, the commercial operators which is very important.

The other approach to green credits is used in Holland. It involves making qualifying energy exempt from an energy tax. The main problem with that is that the long-term security is not there. Taxes can be changed very quickly at the whim of an incoming government. In fact, the right-wing government in Holland cut it in half, so it doesn't present the type of long-term security needed to finance new turbines.

Are market-based obligation schemes better than non-market-based ones such as the Refit type or the NFFO type? Well, non-marketbased supports have had their good aspects. The Refit system in Germany created the European wind energy industry which, you could argue, might never have got off the ground otherwise. It also promoted the advancement of technology. But their time, in my view, has now ended. Wind energy cannot move beyond being more than a niche player in the electricity market if it depends on high feed-in tariffs that come under increasing scrutiny as the percentage of energy coming into the system at the perceived high prices goes up. Look what has happened in Denmark where the perceived cost or extra expense of wind energy eventually led to the scrapping of a lot of schemes.

Non market-based schemes do not drive efficiency and do not give the incentive to the industry to strive to become the dominant technology in the world energy market. So, for the reasons I mentioned, market-based obligation schemes are the best way to move the industry forward. The impact, though, of a move from a type of Refit or NFFO system which is perhaps more favourable to small-scale operators than to large-scale ones, to a fully market-based green credit type scheme has very profound implications for the structure of the industry.

In the major Central European markets and Germany in particular, the focus to date has been on the best price supports and not on the best sites. Wind farms have been located not where wind farms should best be located because of the characteristics of the site, but where the best supports were available. That is fine to get an industry started, but it is not the right way for the industry to develop in the long term. As the market outside the meter was of limited importance, operators could just sit back and wait for their Refit, AER or NFFO cheque to arrive. There was limited market risk. But in the future if you go for a green credit type scheme you will be trading a commodity whose price changes, half hour by half hour. Moreover, the green credits themselves will also be tradable and the price will be volatile although maybe not half hour by half hour.

With green credits, future development focuses on the best, highest-yielding sites so you have the most commodity to trade in the market for the lowest production price. The market for things beside electricity now is of absolutely crucial importance. If you don't understand in detail how that market functions, then you are not going to survive. At worst you'll just get ripped off by people in the market because you don't understand the full value of what you have to sell. This is quite common in the UK where people are paid ridiculously low, or offered ridiculously low prices, for wind output energy because of what the supplier says is the discount due to variability. Market risk is greatly increased and this fundamentally changes the debt-raising capacity of operators in the industry as they move from very low risk AER, Refit or NFFO contracts to quite high risk ones under a renewable obligation or a green certificate scheme.

BANKABLE AGREEMENTS

All wind farm developers require bankable power purchase agreements giving security over fifteen years if they are to raise funds. A long-term contract is required. When you move to a green credit type scheme, now your wind farm is not just producing electricity, it is producing electricity and greenness, both of which have different markets, potentially different customers, different contract structures, different characteristics that will drive their price and their value related to the detail of the market rules that exist. The UK is quite an advanced market in terms how far it has gone down the road of market solutions - not all of which have worked, and some of which have been a disaster. A wind farm in the UK now produces five products: electricity; embedded benefit, [if the grid operator benefits from reduced system losses or not having to spend on strengthening the system because a wind farm begins to supply power, the operator will pay the farm for that benefit]; tax benefit, climate change levy; and then the greenness, which has further associated complexity. The complexity of the contractual frameworks involved in financing such a project changes the nature of the industry; it is not a small-time operator's industry any more. You now aim to build, not one or two farms but hundreds of them producing thousands of megawatts because, quite simply, complexity equals risk equals increased cost of capital. It is an unfortunate fact of life that when we consider transition to renewable energy the views of the bankers are absolutely crucial.

Moving to a green certificate market introduces a lot of regulatory risk and this affects the cost of capital. In order to deal with all these complexities and keep the cost of capital down you need to think about derivative products and other ways of securing your cash flows. And so, from an industry dominated by enthusiasts and by small companies, you move to one dominated by large banks and large energy companies. If you go now to renewable energy conferences in the UK, they are dominated by investment banks, something which would not have been the case ten years ago.

So, if we move to green credits, a major consolidation within the renewable energy industry is inevitable. The reason I labour this point is because when we talk about Ireland being a net exporter of renewable energy it is important first of all to think who will actually be generating it? Who will own it? Who will control it? We need to make our decisions on that basis. Airtricity is in the electricity business first and foremost and it is dangerous to think, like our friend in Montserrat, that electricity is just a pesky by-product of the production of this greenness.

In the UK, having introduced the renewable obligation they effectively said 'well, that's renewable sorted, let's forget about them' As a result they introduced an electricity trading regime, connection policy, grid rules, embedded benefit rules and so forth that completely act against renewables, so generators got value for their agreements but lost on all other fronts. Ireland must avoid that trap and focus on renewable energy as an electricity industry first, and develop the market and the physical infrastructure accordingly, to maximise everyone's opportunities.

Should Ireland export renewable energy? I've had some experience of this with Airtricity trades into Ireland and out of the Republic and since six o'clock this morning (November 1, 2002) we have been exporting wind energy into Northern Ireland. Interconnection is obviously the key to the long-term development of renewables but it can work in both ways so it is not that straightforward. Key issues are the availability of capacity, how it is allocated to people in the market, the costs and the rules. This is because as with everything in the electricity system, interconnector rules demand predictability and controllability; and the cheapest renewable wind has neither of these characteristics. So you have to rewrite the rulebook in order to introduce a regime that would allow exports of intermittent renewables. But to do it on a large scale, the type of scale that we are aspiring towards, requires quite a lot of work, not just on the physical issues, but on the commercial practicalities of how much it costs, and how you deal with your risks and exposures in the market.

Despite the warnings I sound, if we want to get

a renewable industry that is more than a niche

player, then we have to have a market-based

regime. This would be extremely complex and

the ability to deal with market risks would be

crucial. The sector would change utterly but

huge opportunities would be created for Ireland

because we have the best resource. It is therefore

up to us to make sure that we set the rules

so that we can exploit it while minimising the

potential downsides.

This is one of almost 50

chapters and articles in the 336-page large format book, Before the Wells

Run Dry. Copies of the book are available for £9.95 from Green Books. Continue to Press Release from the Commission for Energy Regulation